By Wendy Thomas, Residential Product Manager, Nuaire

Every year the government’s Chief Medical Officer (CMO) is required to produce a report on the state of the public’s health. The 2017 report, released earlier this year, focuses on air pollution as a major threat to public health and calls for tougher standards to combat wide ranging health challenges.

Clearly prevention is better than cure, so the long-term goal has to be to reduce air pollution, but in the meantime what should and could we be doing to protect those most at risk?

Air Pollution: cause for concern?

The Great Smog of London in 1952 was the worst air-pollution event in the UK. It killed up to 6,000 people and 100,000 more were made ill by the smog’s effects. It led the government of the day to introduce the Clean Air Act in 1956, meaning only smokeless fuels could be burnt in certain towns and cities and measures were included to relocate power stations away from cities. It brought an end to the ‘pea-soupers’, as those dense sooty fogs had become known.

And yet, more than 60 years on, once again air pollution is making headline news, with 44 UK cities identified by a recent World Health Organisation (WHO) report as having air too toxic to breathe safely.

Whilst the focus remains on particulate matter, notably PM₁₀ and PM₂.₅, one of the big differences between now and the 1950s is the presence of large quantities of NOx, the collective name for Oxides of Nitrogen (with NO and NO² having the most effect on the environment and human health). The main culprit for NOx emissions is motor vehicles, in particular diesel engines. The WHO annual mean target for NO² is 40 micrograms per cubic metre but in 2015 only six of the 43 UK air quality assessment zones met the annual mean limit value for NO².

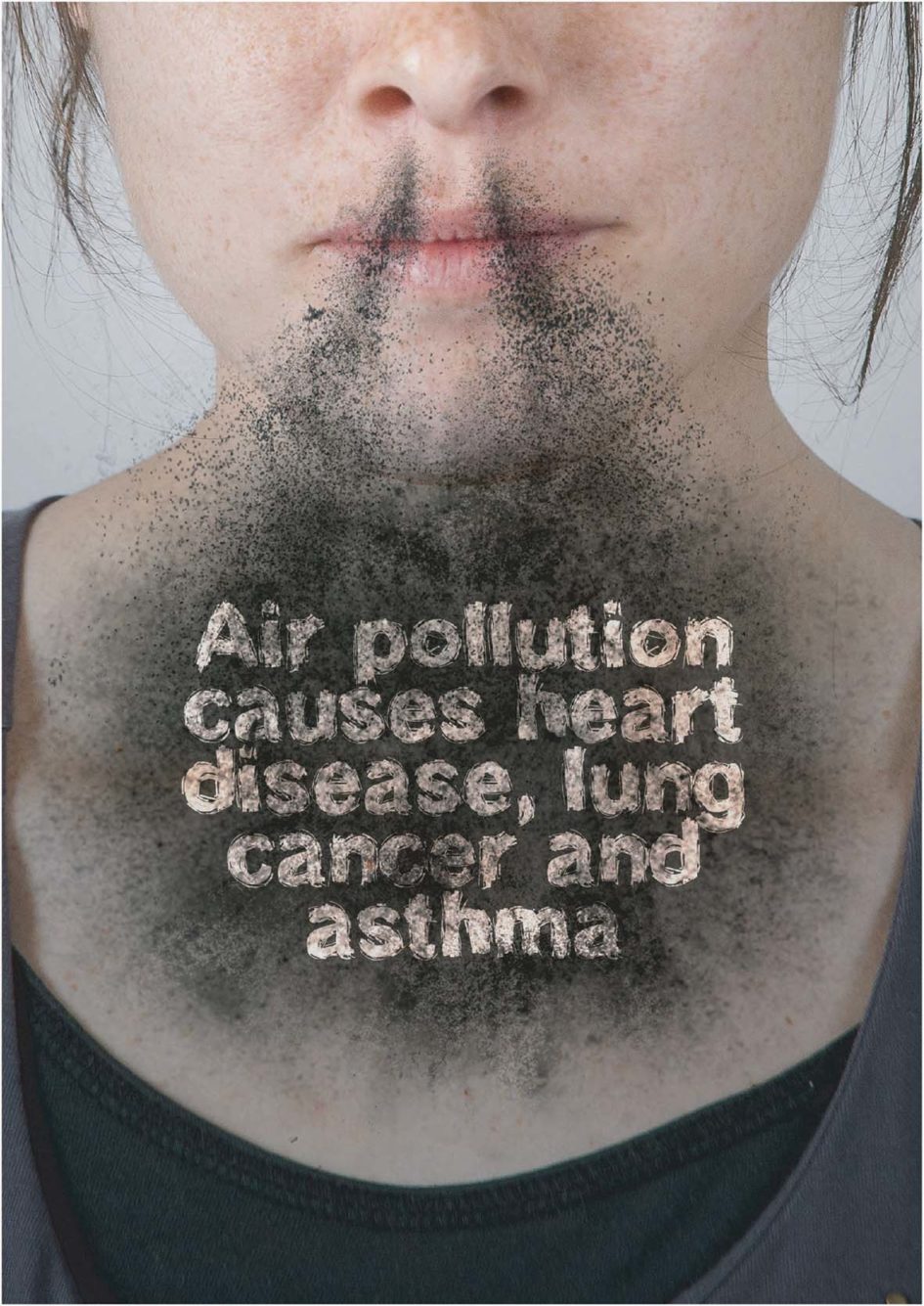

The Impact of Air Pollution

The Lancet Commission on pollution and health estimates the current cost of ambient and household air pollution at £117.30 billion 2015 US dollars in the UK. In London in 2010, it was calculated that PM2.5 and NO² had an associated mortality burden of £1.4 billion and £2.3 billion in 2014 prices, respectively. The number of hospital admissions in London associated with these two pollutants were 2,732 and 419.

The effects of NOx are complex as it reacts with organic substances to form a wide range of chemical compounds that are not only toxic but may cause biological mutations that can reduce overall life expectancy. WHO studies have shown that the cumulative effects of exposure to high levels of NO² in children, for example, result in lung function growth to only around 80% of normal capacity by adulthood.

But it’s not just children who are at risk. Vulnerable groups, such as the elderly and those with underlying medical conditions, are at a disproportionately high risk of respiratory problems. Certainly, it can have a significant impact on people with asthma causing more frequent and more intense attacks. With 5.4 million people suffering with asthma (that’s one in every 11 people and one in five households), the UK has some of the highest asthma rates in Europe and on average 3 people a day die from asthma; that’s a lot of people at risk.

Air Pollution and Deprivation

According to the CMO’s 2017 Report, there is both growing evidence and consensus that deprived groups in England are exposed more to air pollution and are therefore likely to face a greater health impact.

Analysis of the geographical differences in the occurrence and concentration of pollutants shows that these patterns are related to measures of socioeconomic status, with pollution sources and higher concentrations of ambient pollution typically found in more socially disadvantaged areas.

In 2001, of the 2.5 million people resident in areas where the annual mean NO² limit value was exceeded, over half were in the poorest 20% of the population; by 2011 the exceedance population had fallen to 0.6 million due to overall improvements in air quality, but 85% of this population was in the poorest fifth.

Indoor air quality has been less studied, but research in the US shows a positive association between deprivation and poor indoor air quality. Indoor air quality is determined by outdoor air quality, indoor pollutant sources and occupant activity, and physical features of housing including insulation and ventilation.

What Can be Done to Protect the Most Vulnerable?

Reducing levels of particulate matter and NOx are essential in our cities and steps are being taken, but it’s a slow business as it requires major changes such as building schools away from main roads and phasing out diesel cars. But it can be done! German cities now have the right to ban diesel cars from their cities (70 German cities exceeded EU limits for NO² in 2017). What’s more it MUST be done as the population living in UK cities is set to rise to 92.2% by 2030 (from 79% in 1950).

In the meantime, we need to take measures to protect those most at risk and not just those who can afford it. It’s a well quoted figure, but worth re stating here: every £1 spent on improving homes saves the NHS £70 over 10 years. Investing in our housing stock, especially our social housing where some of our most deprived live, is essential for our wellbeing.

Filtering out Pollutants

Carbon filtration remains one of the best options we have for removing pollutants from our homes. Pollutants are attracted to the surface of the carbon and absorbed.

Incorporating a carbon filter into a standard MVHR (Mechanical Ventilation with Heat Recovery) supply air valve that is part of a ducted ventilation system is an effective way to do this as long as access to the filter is quick and simple. Nuaire’s IAQ-VALVE, for example, has a simple ‘twist-and-clip’ bayonet fixture which enables quick release for easy maintenance that can be carried out without the need for tools every two years.

Most MVHR systems however, are designed for new build properties, which is fine for the 170,000 new homes built each year, but what about the 27 million existing homes in the UK? Retrofit options are few and far between, but that is beginning to change as manufacturers react to demand.

MVHR systems remain impractical for existing properties as they require extensive ducting in voids etc. where there generally isn’t any space and it would result in huge disruption and refurbishment. Instead, the industry has turned to Positive Input Ventilation (PIV) incorporating a carbon filter.

PIV units, traditionally used as a cost-effective method of eliminating moisture from the home, gently pressurise a dwelling to expel stale and humid air through natural ventilation points; these are very common in older properties as most of use probably know! PIV units can be mounted either in the loft area of a house, or a hallway cupboard of a flat. By adding a powerful carbon filter inter a PIV unit, existing properties can be benefit from not only reduced concentration but reduced pollution also. In the case of our own Noxmaster system, it removes up to 99.5% of NO² and up to 75% of PM2.5.

Whilst most existing properties can benefit from this combined PIV and carbon filtration system, it’s social housing providers that can use it to make the most immediate difference to the most deprived and vulnerable members of our society. Registered Social Landlords (RSLs) are, after all, the leading suppliers of affordable homes and providers of a wide range of vital welfare services to the most vulnerable in our communities.

It’s time for action when it comes to air pollution and we have to look at both the long and short-term solutions. Reducing air pollution is the goal but can we really afford to wait that long? In the meantime, some of the most vulnerable members of our society are slowly being poisoned in their homes without even knowing it.

Nuaire is a world leader in the design and manufacture of energy-efficient domestic, commercial and renewable ventilation solutions. UK based with over 450 employees worldwide, Nuaire has been at the forefront of the industry since 1966.